The Fight for Medicare for All Must Log Off

The online left will have to go offline in the fight for healthcare justice

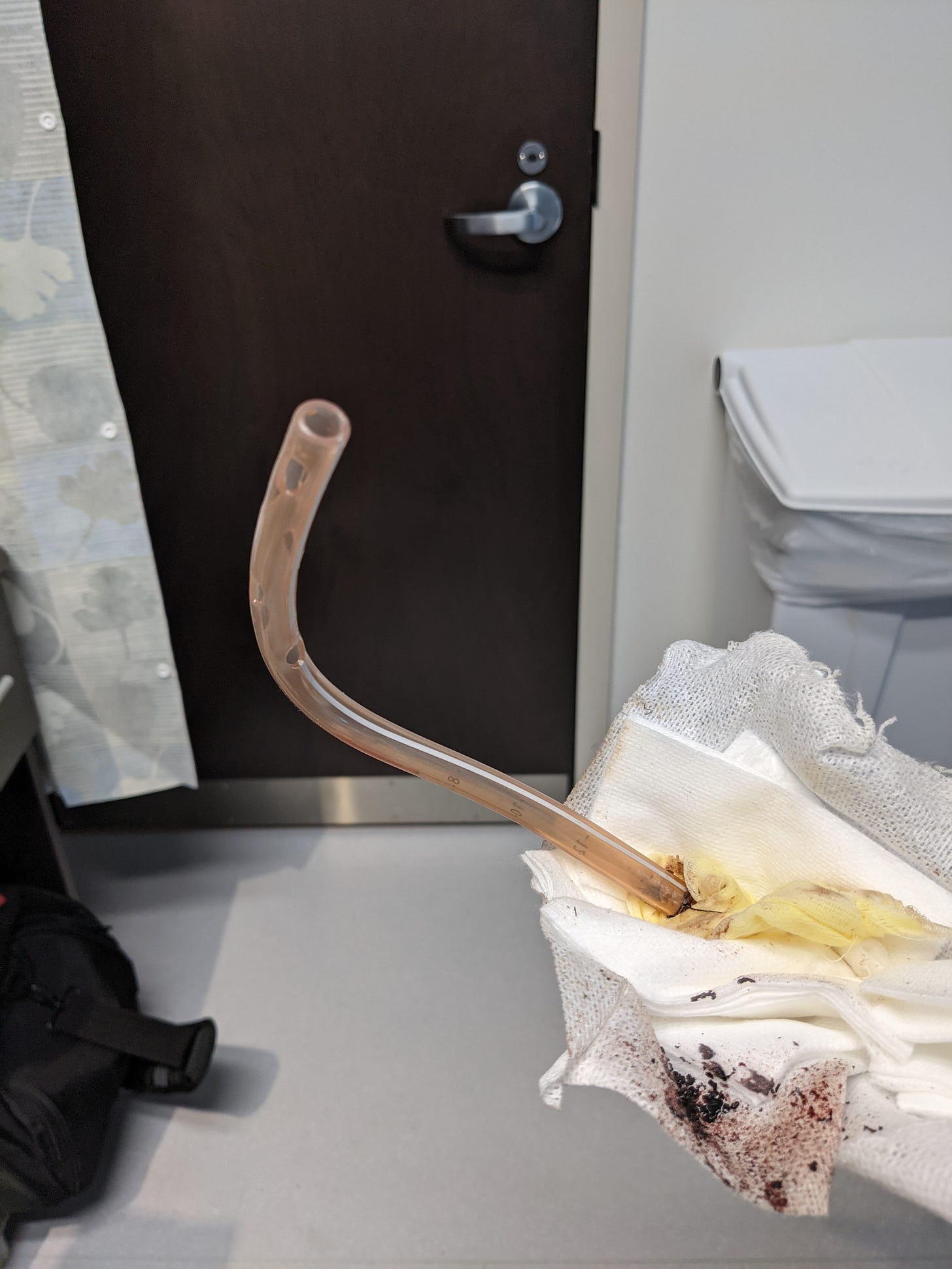

On November 22nd, at some time wedged between late night and early morning, I was involved in a car accident on I-20 heading home east from Atlanta, Georgia. Even now, I’m almost too embarrassed to admit that it wasn’t an accident with another vehicle but me falling asleep at the wheel and drifting left into a concrete median barrier. Upon impact, my car was totaled, my clavicle and several ribs were fractured, and my left lung collapsed. When I woke up in Grady Hospital, located downtown, there was a plastic tube entering my lung, snaking out from beneath my armpit and into a box-shaped drainage receptacle on the floor.

I am uninsured. For a brief moment a couple of years ago, I had insurance under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and paid less than $100 a month for my premium; other than that, I can’t recall the specifics of the plan, including the amount of the deductible. If you live outside of the United States, terms like “premium” and “deductible” are probably just as foreign to you because despite being the richest country in the history of the world, America’s healthcare system is byzantine, does not require an individual to be insured, and their employment can determine whether they even have insurance and what kind. The ACA was an attempt to rectify some of these flaws in our healthcare system while expanding “access” — that infamous, insidious word liberal Democrats love to use when discussing the provision of basic human rights — to more than 20 million Americans.

As the enrollment period coincided with the start of a new year, however, my premium more than doubled and, as a broke-ass college student working part-time in a kitchen, I could no longer afford it. Reflecting back now, there were probably assistance programs for the indigent or unemployed that I could have applied for. But jumping through the hoops of bureaucracy for something I assumed I wouldn’t need — being young and confident that my good health would persist, even though I smoked cigarettes, ate like shit, and didn’t exercise — seemed bothersome and unnecessary.

And yet I never thought that only a few years later I would be lying in a hospital bed, a skinny plastic tube popping out of my left side and draining what looked like blood from my lung into a white box.

I realize how pathetic this may sound to some, but the outpouring of sympathy from the left Twitter community was — and continues to be — overwhelming. The solidarity was palpable despite the fact that I will never meet most of these folks. This was materially evident from the amount raised for my GoFundMe — over $18,000 from hundreds of comrades from all over the country and the world, which was nearly twice the $10,000 goal.

(A quick word on GoFundMe and crowdfunding for medical bills: While millions became insured under the ACA, the soaring costs of out-of-pocket expenses like deductibles, copays, and coinsurance drive people to sites like GoFundMe. About one-third of the donations made through the site are for medical care, and it hosts more than a quarter of a million medical campaigns each year, totaling more than $650 million. But according to a report from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, almost two-thirds of Americans believe that the government should be responsible for providing help when medical care is unaffordable — not GoFundMe.)

After little over a week of lung drainage, eating what tasted like — and probably was — prison food, and incessant poking and prodding from the hospital staff, I was sent home … only to return a few days later because of difficulties breathing due to a buildup of liquid in my lung.

Now I had two tubes inserted into my lung and protruding from my side, looking like something out of the Japanese 1989 body horror film Tetsuo: The Iron Man.

During my second hospital stay, there were two developments of interest. First, I found out that my bill was over $100,000 and counting. The money raised for my GoFundMe now seemed like pocket change lost between the cushions of a couch. I will die of old age before I even get close to paying it off. If I have children — and, to be honest, this is a convincing reason not to — they may inherit my medical debt. Such is the dispassionate and immutable logic of the American system, which reifies medical care so that human beings are merely figures on a spreadsheet.

Secondly, the online discourse around a Medicare for All House floor vote proposed by progressive political commentator and comedian Jimmy Dore hit a fever pitch when two weeks later Chargers running back Justin Jackson endorsed the idea on Twitter: “If @AOC and the squad don’t do what @jimmy_dore has suggested and withhold their vote for Pelosi for speakership unless Med 4 All gets brought to the floor for a vote… they will be revealing themselves. Power concedes nothing without demand.”

Besides this article, I really recommend Briahna Joy Gray’s excellent piece in Current Affairs, “The Case for Forcing a Floor Vote on Medicare for All” for a thorough defense of Dore’s proposal. I won’t retread what Briahna has gone over in straightforward detail, but as an organizer and — paradoxically — a poster, I have just a few thoughts.

I’ll get this out of the way and admit that I’m not a fan of Jimmy Dore. If you haven’t already closed this tab, don’t worry — I won’t go any further. The message is more important than the messenger; a broken clock is right twice a day, et cetera, et cetera. More importantly, Dore is emphasizing something that I learned from my time in party politics and community organizing: If, as a political actor, you don’t have the institutional power to do something, your next best bet is to build a compelling popular narrative and force your opponents to counter it openly, revealing their hand. This would mean moderate and conservative Democrats denying people healthcare during a global pandemic when more than 14 million people have lost employer-based health insurance. Even if progressive lawmakers in the House didn’t have the sufficient numbers to threaten Pelosi’s speakership — which, according to Briahna’s article and basic math, they do — the data is on their side. Eighty-eight percent of Democratic voters support Medicare for All, and most progressive policies are popular with the public regardless of partisanship. A floor vote on Medicare for All would most certainly fail, even amidst a pandemic, but under an incoming Biden administration progressives will have to weigh the opportunity costs of losing some battles in order to win the war.

However, I can’t shake the feeling that there is something insidious about left-wing Twitter, YouTube, Twitch, and podcasts. While I’m extremely fond of the community that has showered me with well-wishes, gifts, and money throughout my ordeal, it is a bubble atomized from the working class, organized labor, and organizers on the ground who do the actual work.

In Thesis 3 of The Society of the Spectacle, Debord writes, “The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as society itself, as a part of society, and as a means of unification … But due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is in reality the domain of delusion and false consciousness: the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of universal separation.” In other words, virtual communities — like left Twitter, et cetera — appear as social reality, components of social reality, and instruments of shared perception all at once.

Yet, their “official language of universal separation” means that these virtual communities and their atomized discourse are inherently removed from action and thus only observational, or powerless. Impassioned tweets, streams, and podcasts are expressions of powerlessness, as the Actually Existing Left itself has no power or very little of it. Can there be any material political outcome from being locked inside of a representation of the world that cannot build power and take action outside of it? Furthermore, can the consumption of radical content really serve as a basis for radical politics?

As if the discourse wasn’t contentious enough — I actually had fans of Jimmy Dore accusing me of not wanting people to have healthcare while I was in the hospital sitting on a $100k-plus bill, uninsured — pundit Benjamin Dixon attacked Briahna Joy Gray, saying that, “she continuously serves the role as a black person who will be the spokesperson for white progressiveness that has not done away with their white supremacy.” My man basically called a fellow black ally an Uncle Tom over a disagreement in strategy.

When powerlessness is the ambient background noise of the left, we’re reduced to being surrogates or “fans” of our favored “team” (Team AOC or Team Dore) and view allies who only disagree with us on tactics as enemies who must be defeated in 280 characters or in a scathing livestream. But that doesn’t mean tactics aren’t worth debating. As author and journalist Ryan Grim recently said in a series of tweets, “You absolutely should. Some maneuvers are dumb, some are smart. Argue that out. But understand that that’s all you’re talking about. Your opponent in those debates is not your enemy. You might even be wrong.”

As of this writing, the speakership vote is less than two weeks away, and there are no plans for pressuring the Squad and the Progressive Caucus to threaten Pelosi. Right now, the “Force the Vote” campaign is just a hashtag.

What is to be done, then? How can the nascent socialist movement that began under Sanders in 2016 flex its muscles four years later during a global pandemic and a freefalling economy in which the biggest corporations are doing just fine, great even?

Maybe it starts with logging off. Coming from me, of all people, that’s rich — I know. I think back, though, to the nationwide uprisings against police brutality and systemic racism that we saw over the summer and that have chilled out with winter’s arrival (though not entirely). This was one of the greatest protest movements in U.S. history. And while it was accompanied by virtual campaigns, most of the work was done in the streets, going toe-to-toe with cops. In the struggle for healthcare justice — which will outlast this pandemic — we better keep that same energy.

I’m ready. Great read!

I read this with dread because I know you're right: posting/tweeting is not organizing, and it does not have any impact comparable to direct action. But so many of us truly don't know what to do, and of course we're also scared of the consequences of direct action, given how governments have doubled down on police power in response to the protests against police brutality. I don't mean to sound defeatist; I think we *have* to act. The question is how.