If you follow me on Twitter, you know that I like fashion, particularly sneakers. As an anticapitalist, it’s my guilty pleasure. I won’t attempt to rationalize my obsession with collecting these cheaply and exploitatively-made mass-produced goods given my politics. A close comrade likes to say, “You’re an agent of capitalism every time you turn on the faucet.” I don’t know if he came up with this himself, and I’m sure similar things have been said about our collective participation in a system of production and consumption designed to enrich not just very specific individuals but a very specific class. And although it is true, leaning too hard into that sentiment can make one feel absolved of any personal responsibility to tear this system down. It can engender inaction, nihilism. So instead of rationalizing, I want to talk about a shirt that I bought.

This is a “vintage” promotional tee for the 1988 critically-acclaimed anime film Akira. I put “vintage” in quotations because a shirt that looks almost exactly like this was produced that year, but this is not that shirt — this is a replica. Besides minor details, like the size tag and text beneath the graphic, it’s a close one-to-one resemblance of the original. There is cracking on the graphic to mimic a worn, aged look. Even the single stitching along the shirt’s hem and the hem of the sleeves is accurate to the way shirts were produced until the mid-90s. In fact, I bought this replica (for more than I should have) because it was advertised as authentic on Depop. When it was delivered and I compared it to pictures of the original, however, small and nearly unnoticeable differences revealed it to be a recreation. Maybe the seller knew that and intended to dupe me. When I asked before purchasing, he seemed to think that it was from 1988 and so did the person who sold it to him.

In the mid-90s, Nike and other sneaker companies began producing retros (re-releases) of iconic silhouettes from the 80s. This is nothing new — since at least the 1900s, fashion has reached backward in time to find inspiration. The last few years have even seen an aesthetic trend of incorporating pre-aged details like distressed materials and yellowed midsoles, the same way you can buy a pair of jeans that already look worn. This may sound odd to someone my Boomer mother's age — “Why would you want to wear something that looks used?” — but aesthetically recreating the past is not unique to fashion. In Mark Fisher’s essay “‘The Slow Cancellation of the Future,’” he contends that some contemporary pop music employs modern audio production technology to mimic the warm, organic crackling of a vinyl record for “the task of refurbishing the old . . . Crackle makes us aware that we are listening to a time that is out of joint; it won’t allow us to fall into the illusion of presence.”1 Synthwave, a retrofuturistic electronic music genre born out of the nostalgic recesses of the internet, doesn’t go as far back as vinyls but emulates the synthesizers and analog production of the 1980s.2

The recreation of crackling in some of today’s pop music, the pre-aging of select Nike retros, synthwave, and the production of a replica vintage shirt are all aesthetic and technical manifestations of hauntology. I will admit right away that at the moment of this writing, I have not read Specters of Marx by Jacques Derrida, in which he coined the word. My most cogent understanding of hauntology comes from Fisher’s application to explore culture and consumer society under neoliberal capitalism, or capitalist realism — a term used by Fisher to describe the near ubiquitous resignation that there is no alternative. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, globalization, finance capital, mass consumerism, and mass media have asserted dominance over not just every sector of the world but of our social relations, our behavior and minds, our hopes and dreams. But this economic and cultural hegemony doesn’t exist purely in recognition of itself; its power and very presence is “haunted not by the apparition of the spectre of communism, but by its disappearance.”3 A recent example that is seared into my memory forever, and maybe yours too, is the presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders in 2020. For many Millennials like me, the Occupy movement in 2011 was formative, a test run, the first time many of us had cut our teeth in the world of left-wing politics. Sanders’ run for the presidency twice was when we actually got to flex our muscles, buoyed by a once-in-a-lifetime candidate. And during his second run in 2019-2020, specifically, we all learned a harsh but valuable lesson: that the Democratic Party, haunted by the dead New Deal coalition and the civil rights movement and which believed that it had finally and entirely exorcised the progressive Left from the party in the early 90s under Clinton, would stop at nothing to prevent a man who identifies as a democratic socialist from becoming their leader and president of the United States. Hauntology, then, is “about the figure of the specter . . . that it cannot be fully present: it has no being in itself but marks a relation to what is no longer or not yet.”4

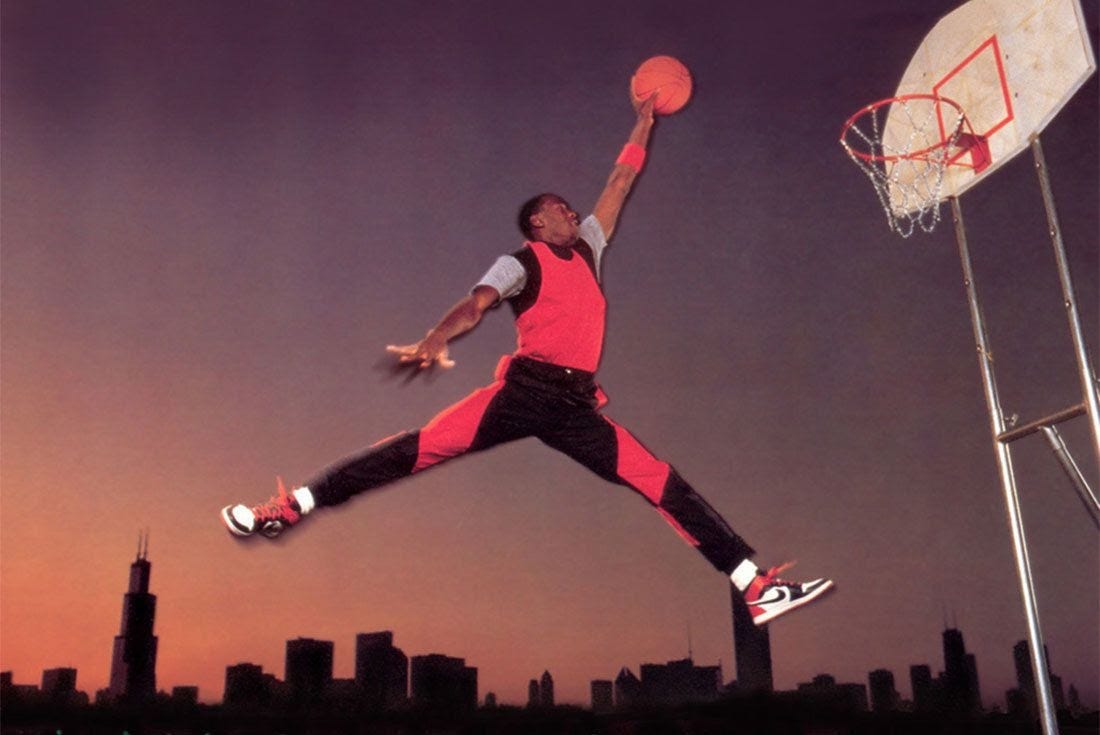

From April to May of 2020, during a pandemic that still claimed well over a thousand lives per day in the United States, Netflix released the ten-part ESPN miniseries The Last Dance, which chronicles Michael Jordan’s final run with the Chicago Bulls in the 1997-1998 season. Featuring exclusive, never-before-seen footage of the team and depictions of American culture spanning the 80s and 90s, the docuseries was a massive success at a time when live sports programming was on hold. It trended on social media timelines and inspired memes and podcasts. StockX, “the stock market of things,” saw a 68% increase in Air Jordan sales the week it debuted, and the site saw its highest traffic ever for the Air Jordan 1 after an episode aired featuring His Flyness wearing the shoe facing off against the Knicks. I didn’t care for basketball growing up, so I never witnessed the Chicago Bulls in their prime, never saw in real time the power and grace of the greatest player ever who would inspire a generation. While watching The Last Dance, I too caught Jordan-mania. But the series is also a deep immersion into the 90s, the decade of my childhood that I recall most vividly with long shadows and persistent sun. I imagine other viewers, especially those a generation older than me, felt that expanding warmth in the pit of one’s stomach attributed to nostalgia, desirous of a time when the Bulls were world champions and life wasn’t so seemingly uncertain and complex. In a statement responding to the popularity of The Last Dance, ESPN said, “As society navigates this time without live sports, viewers are still looking to the sports world to escape and enjoy a collective experience.” This is true, but during social and economic insecurity people escape into the past as well.

Nostalgia surrounding The Last Dance can be characterized as what Grafton Tanner calls pre-Recession nostalgia. It is pervasive wistfulness for an era before the financial crisis of 2008, 9/11, smartphones, and Web 2.0 that

recycles mass media from the years leading up to the first decade of the twenty-first century in order to present a simplistic version of history. Unlike other concepts of nostalgia, pre-Recession nostalgia is most productively understood as both public and private, historical and personal.5

Pre-Recession nostalgia can also be understood as an attachment to form, “to the techniques and formulas of the past, a consequence of a retreat from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms adequate to contemporary existence.”6 What haunts us isn’t merely an imagined idyllic time before global market crashes, terrorism, and the constant interconnectedness of a digital, online world, but what may have been if the creep and then acceleration of neoliberalism (and its consequential crises) was frustrated by an alternative. Inundated and obsessed with the past and locked into a dismal present, we long for lost futures.

In 2018, there were 121 movie remakes and reboots slated for release over the next several years. At least 25 TV show reboots were announced this year, including pre-Recession classics like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Sex and the City. Surely the pandemic has been a fortuitous opportunity for content creators to mine profitable intellectual properties as many stay home or have more time to browse through streaming services. And because of the predictive analytics used by Netflix and others to recommend content to users based on previous preferences, “creative content began cycling over with astonishing speed, thus leading to a culture of recursion.”7 But the internet also powers the nostalgia industry for its structure collapses time, making all of cultural history accessible at once. On Reddit and old-school message boards, fans of media franchises speculate on new stories and versions of their favorite characters, reminisce about the source material, and lament over changes. Sometimes even the actors portraying iconic characters put in their two cents. Andrew Garfield, the second Spider-Man featured in a 2012 reboot after Sam Raimi’s 2002-2007 trilogy starring Tobey Maguire, had this to say about Hollywood studios adapting comic book superheroes for the big screen:

Comic-Con in San Diego is full of grown men and women still in touch with that pure thing the character meant to them. [But] you add in market forces and test groups and suddenly the focus is less on the soul of it and more on ensuring we make as much money as possible. And I found that — find that — heartbreaking in all matters of the culture . . . Money is the thing that has corrupted all of us and led to the terrible ecological collapse that we are all about to die under.

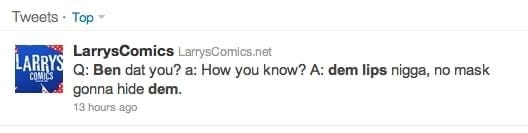

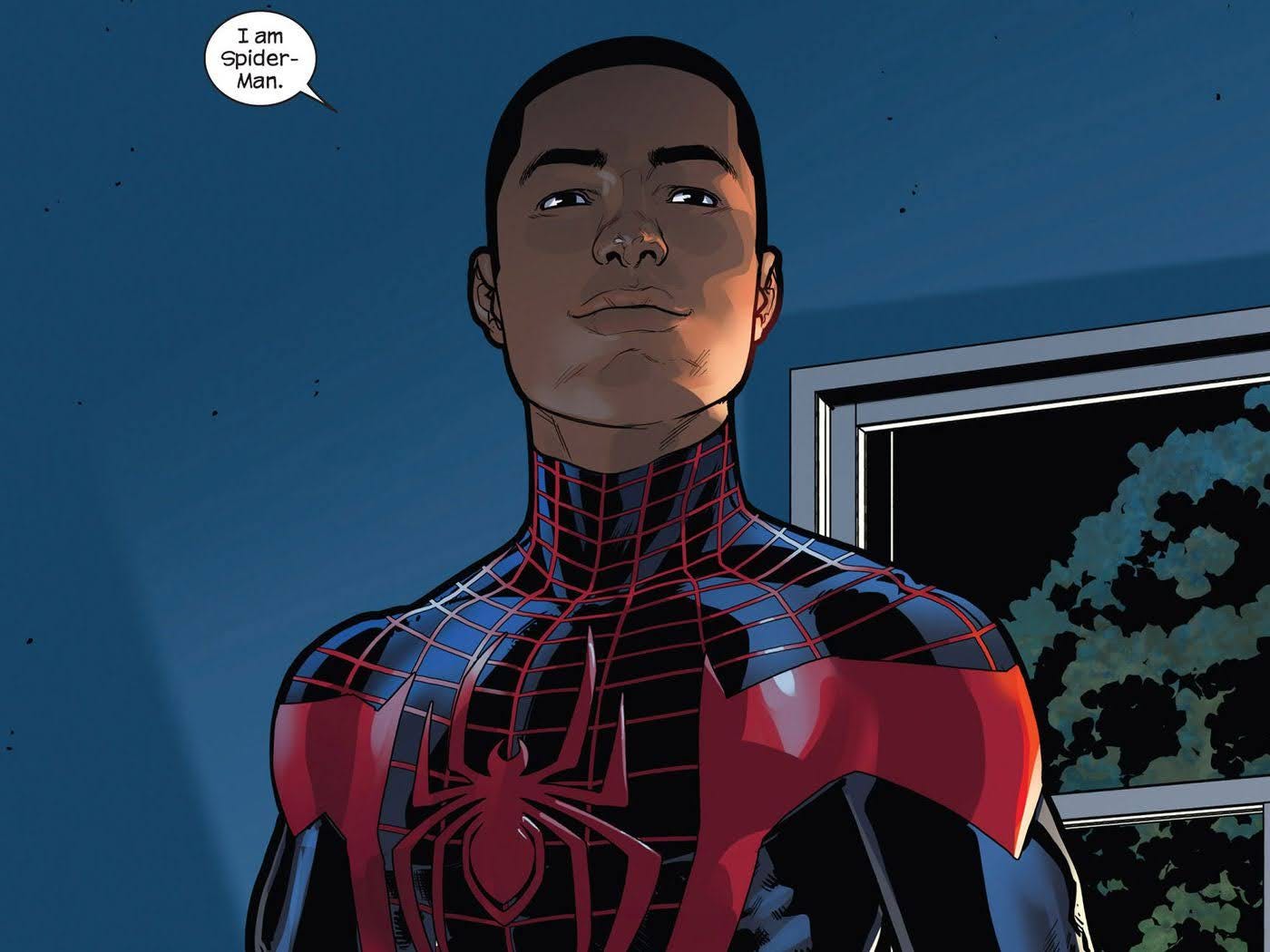

Not all fan criticism is benign, though. Racebending, when a content creator changes the race or ethnicity of a character from being white to non-white, often evokes reactionary backlash from white heterosexual male fans. My first encounter with this was in 2011, the year Marvel Comics introduced Miles Morales, a half-Black and half-Latino Spider-Man from an alternate universe. Browsing comic book forums back then, I came across quite a lot of resistance to this racebending — for some fans, the salt in the wound was their assumption that the white Peter Parker of this alternate universe had to die for Miles to take the mantle. Comments ranged from denial coated in casual racism (“Making Spider-Man anything but white ruins the essence of the character,” or something along these lines) to the more vitriolic like when Larry Docherty of New England retailer Larry’s Comics tweeted this:

Even right-wing radio host Glenn Beck chimed in, saying, “I think a lot of this stuff is being done intentionally. What was it that Mrs. Obama said before the campaign? Because it’s strange how so much of this seems to all be happening.” He was referencing a comment made by Michelle Obama in which she said, “We’re gonna have to change our . . . traditions.” Of course Miles Morales was the primary Spider-Man in the critically-acclaimed 2018 animated film “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” but more recent backlash against racebending includes reactions to Halle Bailey being cast as Ariel in a live-action remake of “The Little Mermaid” and Mindy Kaling voicing Velma in a Scooby-Doo spinoff. Similarly, when DC Comics announced that Superman’s son (who would take over for him as he left Earth for an indeterminate time) was bisexual, angry fans sent death threats to the artists.

According to Drs. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and Amy Stornaiuolo, racebending “is a process by which people reshape narratives to represent a diversity of perspectives and experiences that are often missing or silenced in mainstream texts, media, and popular discourse.”8 It can be a potent cultural weapon against racism, as well as racial capitalism, or a system in which the capitalist class profits from the subjugation and exploitation of race. But even Black fans have argued that racebending can go too far when preexisting Black characters are erased, not to mention that the cultural logic of neoliberalism commodifies identity while leaving the racial social order intact. Nonetheless, racebending is an affront to nostalgia, which tends to sanitize history, to whitewash it and blot out its uglier realities for the marginalized, poor, and working class. Donald Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” is effective because “nostalgia, which peaks during unstable cycles in history, has proven to be a politically powerful tool to unite . . . and divide.”9 In an increasingly tumultuous present when left-wing antiracists and environmentalists are marching and organizing for racial and climate justice, some turn to the white, male, heteronormative past for a secure future.

With climate change no longer a distant apocalypse and worsening material conditions, there is a widespread belief in futurelessness, “a break in the flow of generations, an interruption of human continuity.”10 My generation feels this most acutely, and we will probably serve as the guinea pigs for the nostalgia industry’s latest cutting-edge gimmick: virtual or augmented reality. One could imagine that Facebook’s Metaverse will be offered as an escape into the past, where users can become tourists of history jumping from one era to the next like getting lost in a Wikipedia rabbit hole, free of pesky historical biases and injustice. But it doesn’t have to be this way. By engaging in radical nostalgia, “one crafted from memories of collective resistance, community organization, civil rights, and local politics,”11 we can begin to reclaim the lost futures that haunt us. Still, no matter how firmly we cling to social movements and revolutions of yesteryear, radical nostalgia alone cannot form the basis of serious societal transformation. The American Left, in particular, is all too familiar with losing over the last 60 years, and simply pining for days when it seemed as if a better world was really possible distorts the sacrifices made by those before us and the viciousness of their enemies. Things weren’t easier then by far; any gains made were fought and won with blood and loss. Revolutionary culture was instrumental in disseminating ideas of resistance and change through newspapers, pamphlets, literature, plays, films, and music.

To believe that we can construct an alternative culture that exists outside of today's mainstream underestimates the influence of cultural hegemony and assumes that working class people are objective depositories for the ruling class to dump hegemonic ideas into. If this is the case, then all of popular culture — which is really bourgeois culture — must be thrown out so that we can start over, yet this time authentically for the “real” working class. (Which begs the question: Who would get to decide what gets discarded and who is a “real” proletariat?) Rather, people interact with the media they consume, either rejecting falsehoods and trivialities, or recognizing themselves and their experiences. This dynamism between the working class and cultural hegemony is what Stuart Hall calls “the dialectic of the cultural struggle”:

. . . there is a continuous and necessarily uneven and unequal struggle, by the dominant culture, constantly to disorganize and repopularize popular culture; to enclose and confine its definitions and forms within a more inclusive range of dominant forms. There are points of resistance; there are also moments of suppression.12

The old becomes new again; what was once taboo and subversive is now socially acceptable (and profitable). Understood in this way, popular culture (like history) is never fixed but holds within it contradictions and repeated contests over power and influence between the classes. The Left should exploit these tensions and fissures, building a revolutionary popular culture that isn’t just an exclusive club or echo chamber or menagerie of haunting victories but is focused on “the relation between culture and questions of hegemony . . . the class struggle in and over culture.”13 Doing so in the here and now might be one way to wean ourselves off pre-Recession nostalgia, to exit a neoliberal culture of recursion, and to challenge capitalist realism and futurelessness. There is no true refuge in the past, nor is a better world waiting for us — we have to make it.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2014, pp. 12+.

Tanner, Grafton. The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2020, p. 50.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2014, p. 19.

Hägglund, Martin. Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 2008, p. 82.

Tanner, Grafton. The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2020, p. 57.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2014, p. 11.

Tanner, Grafton. The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2020, p. 79.

Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth, and Amy Stornaiuolo. “Restorying the Self: Bending Toward Textual Justice.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 86, no. 3, 2016, p. 313.

Tanner, Grafton. The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2020, p. 86.

Lifton, Robert Jay. Superpower Syndrome: America’s Apocalyptic Confrontation with the World, Nation Books, New York, NY, 2003, p. 163.

Tanner, Grafton. The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech, Zero Books, Winchester, UK, 2020, p. 11.

Duncombe, Steven, and Stuart Hall. “Notes on Deconstructing ‘The Popular’.” Cultural Resistance Reader, Verso Books, New York, NY, 2002, p. 187.

Ibid., 189+.

stellar essay, Aaron! thank you for consolidating into words so many of the disjointed thoughts i've been having over the past few years. looking forward to reading more of your work and subscribing :)